Who Really Was the A&R?

The name sounds cold, almost administrative: Artists and Repertoire. In theory, the person in charge of artists and their catalog. In practice, it was the filter between music and the world, at least back when DIY distribution didn’t exist.

The one with the musical ear. The only one able to tell if an artist was worth something before the market did. Or at least, that’s the legend.

For decades, the A&R was the most powerful yet invisible figure in the music industry. They didn’t play, write, or produce, but they decided everything, who got in and who stayed out. If an artist ended up on a record, on the radio, or on a stage, it was because somewhere, in a smoky office full of tapes and contracts, an A&R had said yes. A yes worth millions. A no that could erase a career.

Donald Passman, in All You Need to Know About the Music Business, put it clearly: “In the early days, A&R executives were the true creative architects of the business. They found the talent, picked the songs, and guided the sound.”

They were the ones with the radar switched on. Not bureaucrats, but people able to recognize a new sound before it even had a name. They went out to clubs, bars, small festivals, basements filled with broken amps. They spent nights chasing something that sounded different, something that broke the pattern. No algorithms, no data, no focus groups. Just ears, instinct, and a level of risk almost no major label would dare to take today.

In the golden age of the record industry, the A&R was part anthropologist, part gambler. Where others saw confusion, they saw signals. One foot in the streets, one in the boardroom, translating raw cultural energy into something the market could understand. John Hammond at Columbia heard the potential of Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Bruce Springsteen when they were still nobodies. Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic didn’t follow trends, he created them, turning soul into pop culture. And George Martin, with the Beatles, proved that the work of an A&R wasn’t just about finding artists, but understanding them better than they understood themselves.

Back then, everything that passed through an A&R reached the market. Not because it was always brilliant, but because there were no other doors to walk through. Labels were real gates, and A&Rs held the keys. Deciding who got recorded, pressed, and distributed meant deciding who got a future. In an era of vinyl, CDs, and shelves, the filter mattered more than the talent.

As Passman wrote: “A&R departments are the heart of every record company. They decide what gets recorded, and therefore what the world hears.” If they didn’t pick you, you didn’t exist.

It was a romantic and brutal job: one yes could change a life, one no could bury it. But back then, scarcity made sense. Pressing a record was expensive, every release was an industrial bet. Shelf space was limited. Radio time was finite. Playlists didn’t exist.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the role exploded. The A&R became power itself. Not just a scout, but a shaper. Rick Rubin is the perfect example: a bearded kid in flip-flops who, from his NYU dorm room, founded Def Jam and rewrote the language of American music. He didn’t have an office, he had an ear. He realized hip-hop wasn’t a fad but a cultural movement, and that the fury of the Beastie Boys or the voice of LL Cool J could speak to an entire generation. Rubin wasn’t looking for “the next big thing.” He was hunting for a new sound, a code no one had dared to release yet. He worked like a punk scientist, stripping things down, cutting the noise, leaving only rhythm and voice.

In that era, the A&R wasn’t just finding talent, they were defining the direction of an entire generation. Their instinct didn’t predict what worked, it created it.

Then the power began to slip. Not because of the internet or streaming, that would come later, but because something more subtle changed. When distribution stopped being a gate and became a flow, the A&R’s power started to fade. You no longer needed to convince someone to enter the market. You just needed to upload. Selection turned from vertical to horizontal. Labels no longer decided what the audience would hear, the audience decided what the labels would chase.

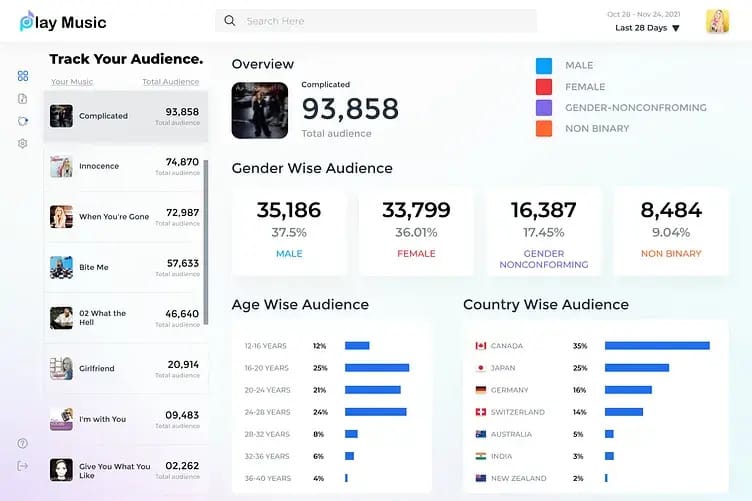

The A&R didn’t disappear. It evolved. From explorer to analyst. From discovering artists to interpreting trends. Today, an A&R spends more time on Chartmetric than in clubs, tracking growth curves, engagement rates, and follower velocity.

Passman sums it up perfectly: “Today’s A&Rs are also data geeks. They study the numbers, the trends, and the metrics, but the best still trust their ears.” And that’s where the game still lies, between those who read data and those who can still feel.

The most human job in music risks becoming a dashboard task. Labels have started behaving like venture capital funds: they don’t build momentum, they buy it. They sign artists only when the numbers already prove them right. It’s the same shift we’ve seen in tech: less instinct, more spreadsheets; less vision, more validation. The modern A&R doesn’t take risks anymore, they manage them.

In the end, A&Rs and venture capitalists do the same job. They both live in uncertainty. They both look for the exception. They both bet before the data makes sense. An A&R might sign ten artists knowing only one will break through, but that one will pay for the rest. A VC invests in ten startups hoping one becomes a unicorn. Same logic. The power law.

In the ‘70s, an A&R signed an artist for a vision. Today, they do it for a prediction. The same way investors moved from charisma to traction. Everyone’s looking for “calculated risk.” But calculated risk isn’t risk at all, it’s just statistics wrapped in storytelling.

Labels are funds. A&Rs are early-stage investors. But the real unicorns, the ones that last, don’t come from spreadsheets. They’re born from an intuition you can’t explain but recognize instantly. The same feeling John Hammond had when he first heard Dylan, or any A&R still gets when they realize a voice in front of them doesn’t sound like anyone else. It’s the difference between reading the market and anticipating it.

Today, though, that kind of instinct doesn’t just belong to record execs. It belongs to anyone willing to discover, share, and push. Every time a fan posts about an unknown artist, every time a TikTok clip goes viral, every time an independent playlist lands a track in front of thousands, it’s the same process, just distributed. Everyone has become a micro A&R. No title needed. Just ears and conviction.

Social platforms have turned discovery into a collective act. The difference is that today that instinct is visible. A video, a trend, a reel can change an artist’s life more than a thousand meetings in Los Angeles. What used to be a once-in-a-lifetime break is now an algorithmic ripple. The dynamic hasn’t changed, someone listens, feels something, and decides to push. It just happens in public now, at global scale.

Maybe we’ve always been A&Rs without knowing it. How many times have you told a friend, “I’ve known this band for three years”? Now that moment leaves a trace. Every click, every listen, every share can become a small movement. For the first time, we can measure it and finally, give it value.

That’s where Fankee comes in. The idea that discovery isn’t consumption, it’s participation. That music doesn’t just belong to those who create it, but also to those who recognize it first. That value isn’t only in creation, but in connection. The A&R of the future isn’t a gatekeeper in an office, it’s a community of people who listen, share, and believe. A distributed system of ears, passions, and instincts moving together.

Once, a signature could change a life. Now, ten genuine shares can launch a career. Maybe we’ve always been A&Rs, we just didn’t have the tools to prove it.

The truth is, hits don’t happen by accident. They explode because they anticipate something, a need, a feeling, a code the culture hasn’t yet found words for but already feels. Every hit is an early signal, a sound that translates what people want to live through at that moment.

And social media, for better or worse, is exactly that: the emotional thermometer of the world. Inside every viral sound, every meme, every TikTok loop, there’s a collective desire taking shape. The A&R of today isn’t the one discovering an artist in a bar, it’s the one reading these waves before they become tides. They don’t just read numbers; they listen to what moves people, what resonates in behaviors, memes, and language.

That’s why discovery today isn’t an individual act anymore. It’s collective. People, communities, platforms, all functioning as a distributed radar, each picking up a piece of what matters. And now, for the first time, this process is visible, traceable, and valuable.

Fankee exists to give shape to that new collective instinct. Because if music is the mirror of a time, then those who reflect it first, who discover it, push it, tell its story, are part of its creation.

🎧 TRACK(S) OF THE WEEK

What’s been spinning while building, dreaming, or burning it all down. Join my playlist — and send me your favorite track. I’ll feature one next week with a proper shoutout.